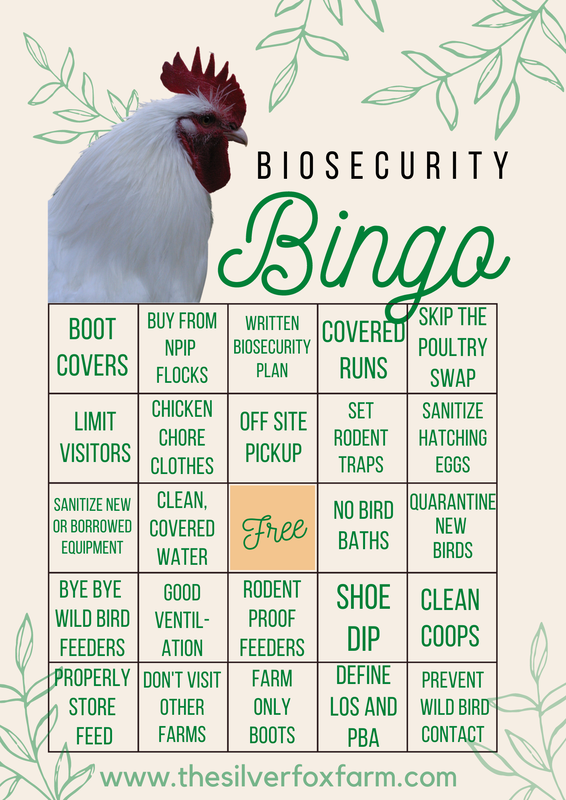

What is a Biosecurity Plan?A biosecurity plan is a set of measures put in place to prevent the introduction of disease into a flock, or keep disease from spreading within a flock. While the phrase “biosecurity plan” might bring to mind industrial scale poultry houses, these precautions also have a place in a backyard flock or small scale farm. Biosecurity plans don’t have to be fancy. They are composed of simple, everyday things you can do to protect your birds from disease and keep them healthy. In this post, we’ll break down what each element of a biosecurity plan means, and give examples of how they can be applied to your own flock. Disclaimer: I’m not a veterinarian, and nothing in this article should be construed as veterinary advice. Please contact your vet for animal care or guidance. Why are Biosecurity Plans Important Right Now?Biosecurity plans are a timeless part of good animal husbandry. But If you spend any time in online poultry circles, you’ve probably been hearing a lot about biosecurity plans lately, due to the recent High Pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak. Avian Influenza (AI) is most commonly spread to domestic flocks through exposure to wild bird feces, which contain the virus in high concentrations, and direct contact with wild birds. AI is most associated with waterfowl and shorebirds, but other bird species do spread the disease. AI can also be transmitted to mammals, including marine mammals. AI strains are divided into two categories, High Pathogenic Avian Influenzas (HPAI) and Low Pathogenic Avian Influenzas (LPAI). While the effects of HPAI can vary in wild bird species, the disease is devastating to poultry. In poultry flocks, HPAI is highly contagious, spreads rapidly, and has a high mortality rate: up to 100% within days of onset. This is in contrast to Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI). LPAI can linger undetected in a flock, causing little to no symptoms. You’ll know (and quickly) if your flock has HPAI, but LPAI might not show itself unless triggered by a stressor in your flock. HPAI is a reportable disease, and in the case of an outbreak, the USDA will “depopulate,” or cull, any surviving birds in order to prevent the spread of this disease. If you suspect HPAI in your flock, call your state vet immediately. Signs of HPAI include:

During this most recent HPAI outbreak, sudden death without other symptoms preceding it is common, so a sudden increase in unexplained mortality should be reported as well. As NPIP participants, our flocks are tested twice a year for Avian Influenza, and we recommend purchasing from NPIP certified, AI clean flocks whenever possible, to reduce the risk of introducing any AI strain into your flock. (NPIP stands for National Poultry Improvement Program; participating flocks are tested and certified to be free of certain poultry diseases, and this program helps us meet the importation requirements for shipping across state lines.) More HPAI resources: Is Biosecurity Necessary for My Backyard Flock (& What About Free Ranging?) Avian Influenza is just one of the many things a good biosecurity plan defends against. Biosecurity measures will help protect your flock against all avian diseases and parasites, which spread through contaminated equipment, surfaces such as shoes or tire treads, and wildlife exposure, among other things. A biosecurity plan might seem unnecessarily constricting, especially if you only have a small backyard flock. Many biosecurity plans and recommendations are written with large scale, indoor operations in mind, but each principle is applicable to even the smallest flocks, in ways that are completely manageable and accessible to the backyard chicken owner. Keep that in mind when reading the biosecurity plan elements we share in the next section. In a backyard flock that is not certified, tested, or shared with others, how to apply biosecurity principles is a personal decision. This article is meant to provide information and guidance to help you understand biosecurity principles and make a biosecurity plan that works for you and your flock. In order to do that, we’ve provided as many ideas and examples as possible for you to consider. Don’t let that overwhelm you–make a plan that is doable, fits your comfort level, and makes sense for your space. Your plan can be simple, everyday habits that protect your flock. For example, having a dedicated pair of shoes to wear when in your chicken area is one of the easiest, most effective ways you can protect your chickens. And yes, you can still free range and have a biosecurity plan! In addition to a basic, everyday plan, we recommend having a second level to your plan that defines what added biosecurity measures you will take during times of higher risk of disease transmission–like right now, during the current HPAI outbreak. What extra measures will you take to increase your flock's safety during these periods? For example, while we generally allow some of our flocks to free range, we've stopped free ranging during this HPAI outbreak, to protect our chickens from exposure to wild birds. The Elements of a Biosecurity PlanIn this section, we will go through the 14 principles of a biosecurity plan as laid out in the NPIP Standards, and discuss the various ways those principles can be put into practice in your backyard flock. 1. Biosecurity Responsibility: Any poultry operation should have an appointed Biosecurity Coordinator, who is responsible for implementing, evaluating, and updating the biosecurity plan. For the Backyard Flock: Appoint a home expert. One or two members of your household should take the lead on learning about biosecurity, making and implementing a plan, and updating as needed. Review annually or during times of high risk. 2. Biosecurity Training: An operation’s program should have training materials, and all personnel and new hires should be trained in biosecurity practices. For the Backyard Flock: Share your biosecurity plan with the rest of your household. Keep a written version of your plan handy, on paper or in a Google Doc. This will make it easy to train anyone who may care for your flock in your absence, and you can easily train a caretaker on short notice in the case of emergencies. 3. Line of Separation: The LOS separates poultry and the poultry house from potential disease agents. It’s generally defined by the walls of the poultry housing. For the Backyard Flock: Of course, unlike large scale poultry operations, backyard birds enjoy lots of time outdoors, either in runs or free ranging. It’s inevitable that backyard chickens will be exposed to some kind of risk, because they live outside. That’s okay–it’s still important to define an LOS for your space, so that you can develop biosecurity protocols for entering it. For your backyard flock, think of your LOS as your chickens’ living space, or wherever they spend their days. Your LOS could be a coop and run, the area within your chicken tractor, or a backyard where your birds enjoy free ranging. In your plan, consider defining and enforcing a secondary LOS for times when there is a high risk of transmission, such as during the HPAI outbreak. For example, your LOS might be your fenced in backyard, but during times of high risk, you could pause free ranging and limit your flock to their coop and a covered outdoor run. However it’s defined, when entering the LOS you should take precautions to prevent the spread of disease on your clothing and shoes. Some recommendations for crossing the LOS:

Why the focus on boots? Avian diseases can travel on surfaces and the soles of our shoes, so no matter the risk level, we always use a dedicated pair of boots when doing farm chores. These boots never leave our property, and our “off-farm” shoes only take us from the front door to the car. During high-risk periods, we cover our farm boots with boot covers as well when entering our chicken runs or coops. We also have dedicated farm clothes–I’m a huge fan of Dickies’ coveralls, because they are easy to take on and off as I go between my farm chores and indoor tasks. Having a dedicated pair of shoes and clothing is a simple but incredibly effective biosecurity measure. 4. Perimeter Buffer Area: The PBA is the area surrounding the poultry housing that separates the poultry area from other areas of your property. It includes housing, equipment storage, feed bins, compost piles, etc. For the Backyard Flock: You’ll want to consider protocols for entering this space as well. Dedicated shoes and clothes are great, and can be the same ones you use for the LOS–especially since the LOS/PBA often overlap in a backyard set up. At our farm, our whole property other than where we park and live is essentially chicken land. During most times, our birds can free range, we have the same safety protocols for our LOS and PBA, and dedicated clothing that we wear for all chores. However, during times of higher risk, like now, we put a pin in free ranging and define a very clear LOS and PBA. Past the LOS, we take greater precautions such as covering our boots so we can’t accidentally track wild bird feces past the LOS. 5. Personnel: I’m guessing that you don’t have employees taking care of your backyard flock, so let’s discuss this in terms of people. How will you reduce the risk of disease transmission to your flock through people–visitors and yourself included? Again, this might change depending on current risk levels. For the Backyard Flock:

6. Wild Birds, Rodents, and Insects: Obviously, it’s easier to protect birds in a large-scale, enclosed poultry operation from wildlife. Your backyard flock, living outside, is sure to meet a bird or rodent or two. However, wildlife is a source of disease for your flock, so it’s important to minimize exposure where you can. For the Backyard Flock: A lot of this biosecurity piece relates to coop design. For example, covered runs protect your flock from wild bird feces, and hardware cloth secures your coop and run against small animals and birds. Building your coop to keep wildlife out goes a long way toward keeping your flock safe. (A well built coop prevents disease in other ways, too. A nice, dry coop with great ventilation will help protect their sensitive respiratory systems from viral and bacterial infections.) Other best practices include:

7. Equipment and Vehicles: This point covers protocols for disinfecting equipment and establishing traffic access and patterns. This piece of the biosecurity plan is important, because avian diseases can spread via shared equipment or tire treads. This is one of the many reasons we don’t do farm tours, and do all of our local pickups off-site at a local park. Visitors are a significant biosecurity risk, not only through clothing and shoes but also through their vehicles. Of course, our friends and family do visit, and we know yours do, too. That’s okay! While large scale operations might require the tires of vehicles to be sprayed with a sanitizing wash before entering the premises, you don’t have to hose down your mother-in-law’s car to keep your flock safe. Consider the following precautions instead: For the Backyard Flock:

8. Mortality Disposal: This part of a biosecurity plan covers how to dispose of deceased poultry in a way that does not attract wild animals or promote cross-contamination. For the Backyard Flock: Losses are a sad but inevitable part of chicken keeping. While the occasional death is normal, you’ll still want to take precautions when disposing of the body. Attracting wildlife is bad for your flock, and the body itself could potentially spread disease. It’s best to dispose of the body on-site; burial (at least two feet deep) or burning are the recommended methods. I know that burning your favorite pet might not be emotionally doable for folks. If burial isn’t possible (the ground is frozen, etc.) you might be able to find a local vet to help with disposal. 9. Manure and Litter Management: Manure and spent litter should be removed and disposed properly, to reduce exposing the flock to disease, and in a way that limits access to wild animals. For the Backyard Flock:

10. Replacement Poultry: This item covers biosecurity protocols related to adding birds to your flock, including where they are sourced from and how they are transported. For the Backyard Flock:

11. Water Supplies: Drinking water for flocks should be sourced from supplies such as wells or municipal systems, and if surface water is used it should be treated. For the Backyard Flock:

12. Feed and Litter Replacement: Feed and bedding should be stored and maintained in a way that prevents exposure to rodents and wild birds. For the Backyard Flock:

13. Reporting of Elevated Morbidity and Mortality: A biosecurity plan should define what elevated morbidity and mortality levels are for a given poultry operation, and high levels should be reported and investigated. For the Backyard Flock: The occasional illness or loss is normal in a backyard flock. It’s smart to be prepared in advance with a plan for what you’ll do if you suspect an outbreak of disease in your flock. Is there a vet near you that will see poultry? This is important to know ahead of time since avian vets can be hard to find, and not all vets are accepting new patients. Establish a relationship with a local vet before you have an emergency, if possible. Search for a local avian vet here and here. If you suspect a reportable disease such as Avian Influenza, report it to your state vet. Find your state vet here. 14. Audit: Good news! Unless you are an NPIP participant with tens of thousands of birds, you are exempt from auditing! But it can’t hurt to audit yourself, right? Review your biosecurity plan at least annually, make changes as necessary, and celebrate the fact that you are doing good things to protect your feathered friends! What Will Be in Your Biosecurity Plan?So--now that you're familiar with all the major points of a biosecurity plan, it's time to make your own! For your convenience, here's a biosecurity template that you can print, mark up, and share with your flock's other caretakers. Do you have any questions about biosecurity for your backyard flock? Ask away in the comments below. Did you like this post? Then you might also enjoy... Coop Fundamentals: Essential Elements for Every Chicken Coop What's in My Chicken First Aid Kit? How to Grow Lentil Sprouts for Your Chickens

1 Comment

3/28/2023 11:41:38 am

I liked how this post shared that a biosecurity plan can prevent the introduction of disease into a flock. My friend told me that his farm needs sheep dipping. I should advise him to look for a sheep dipping with vast experience in the field.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Hi, I'm Maeg.Welcome to our blog! Categories

All

|

©

The Silver Fox Farm