|

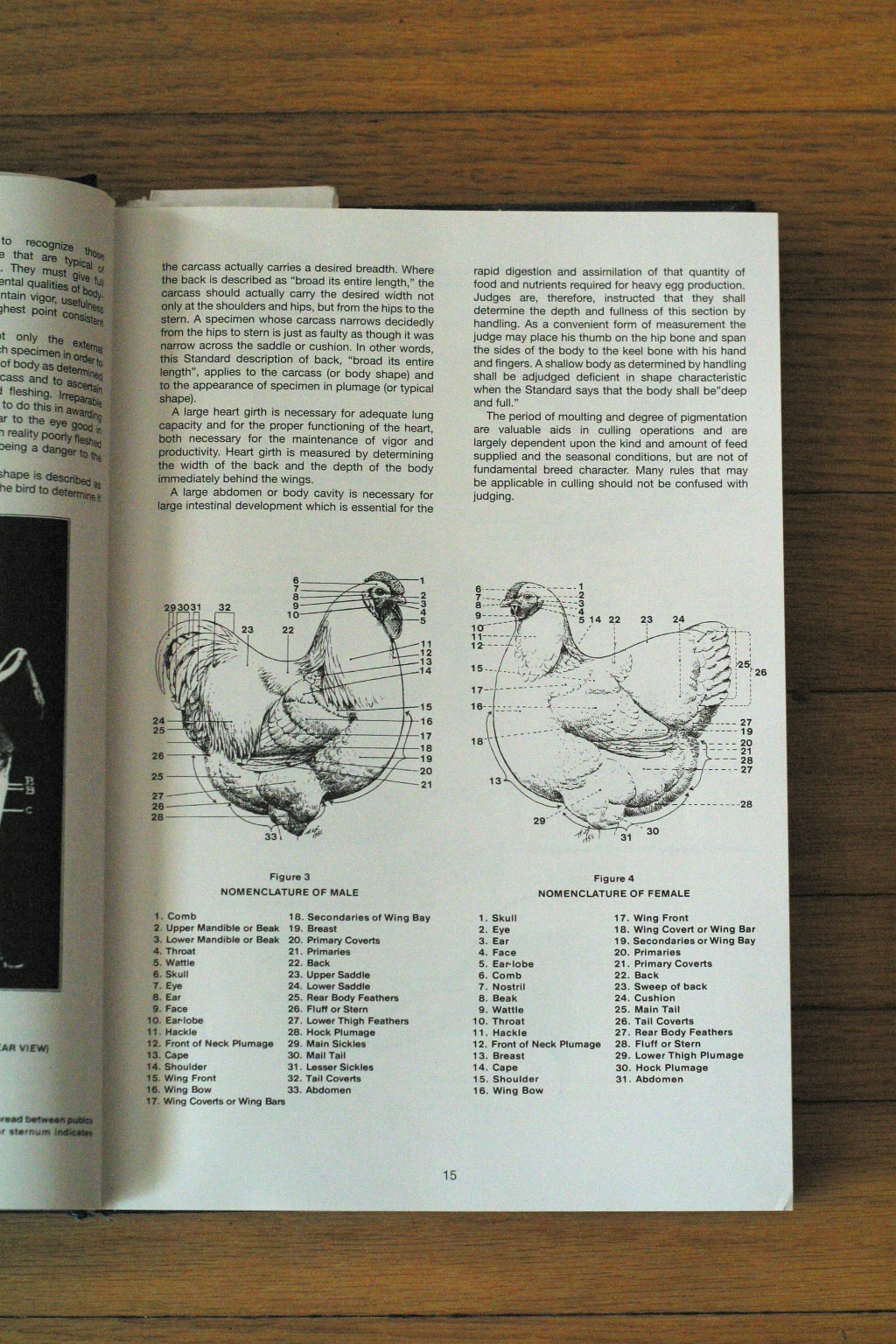

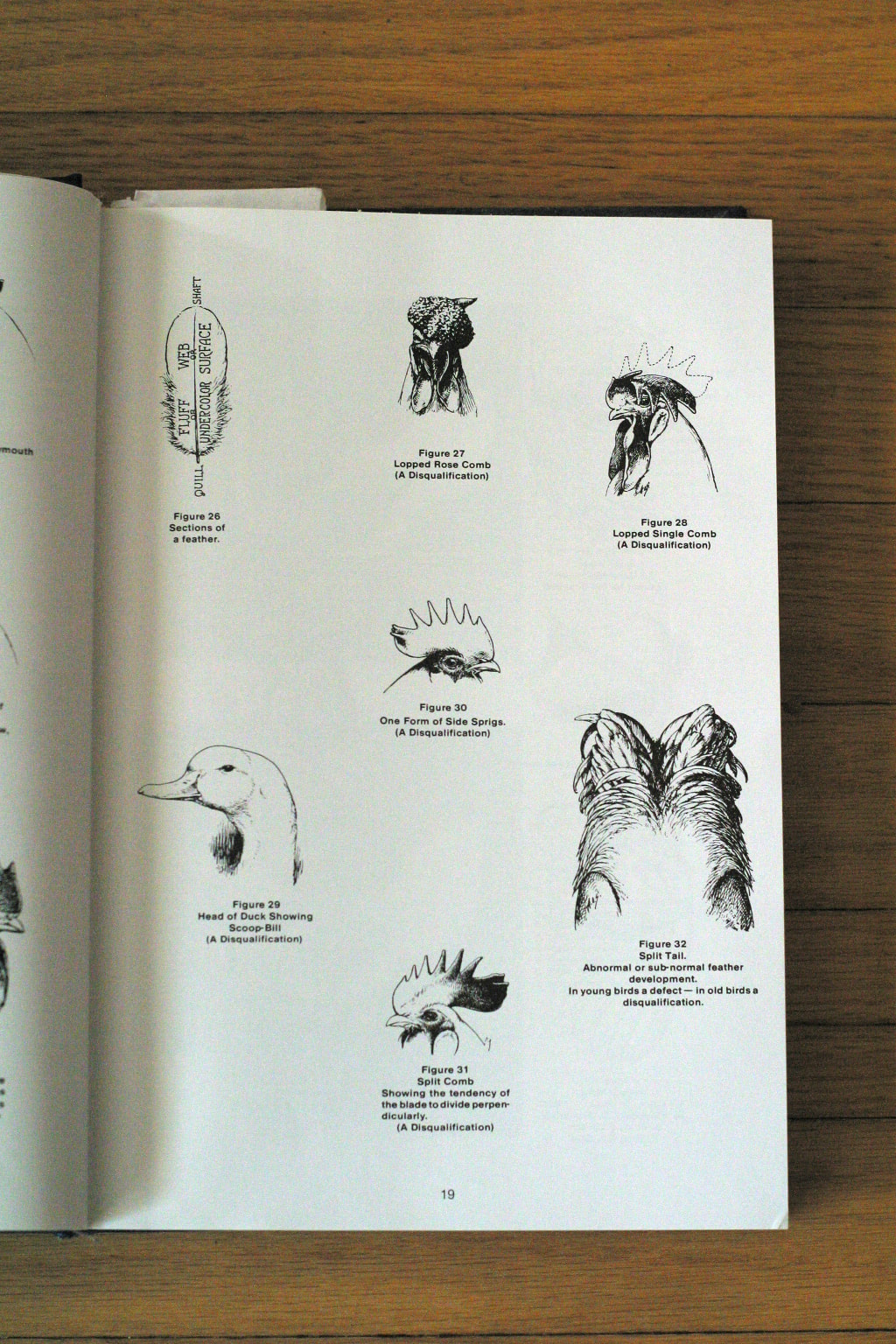

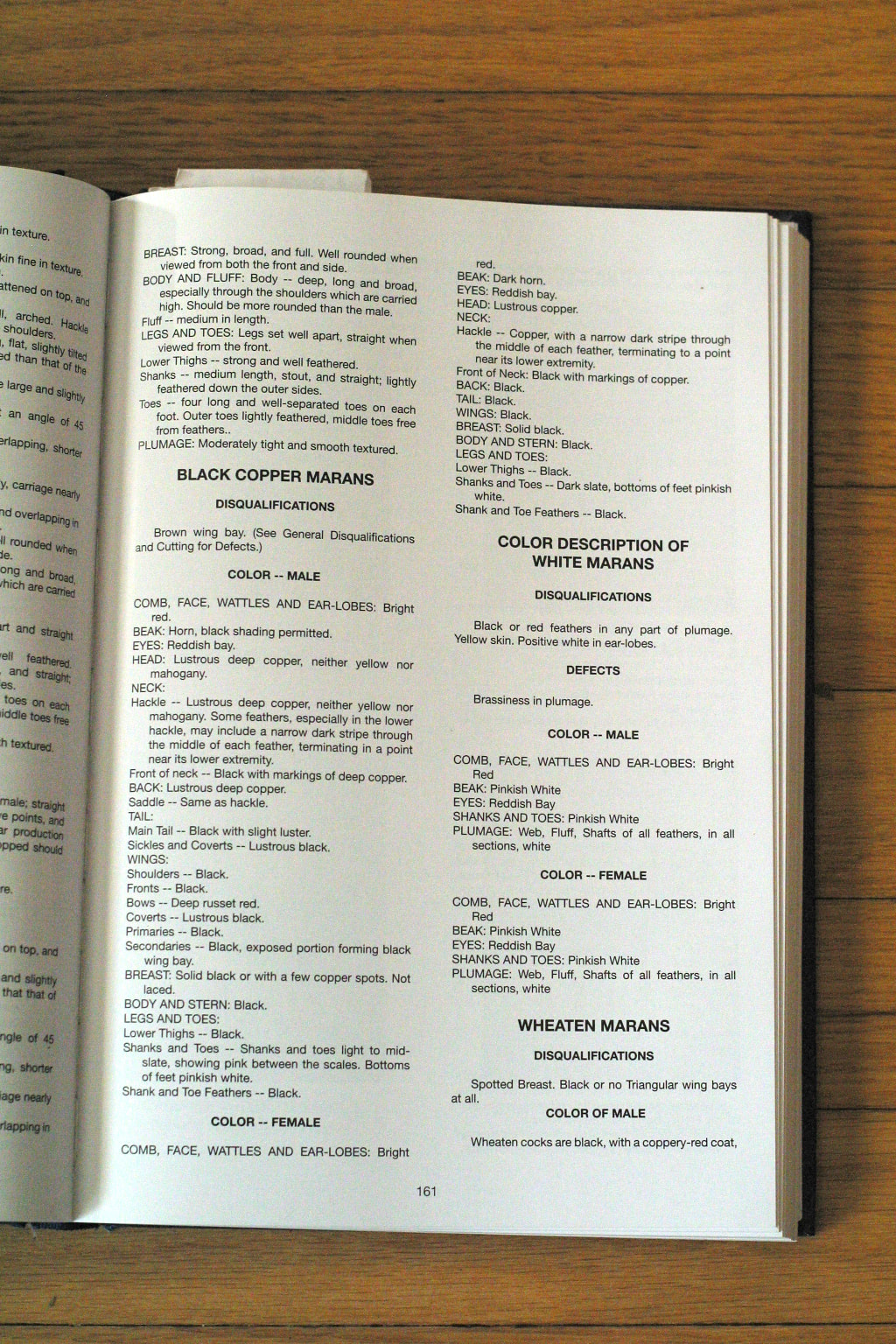

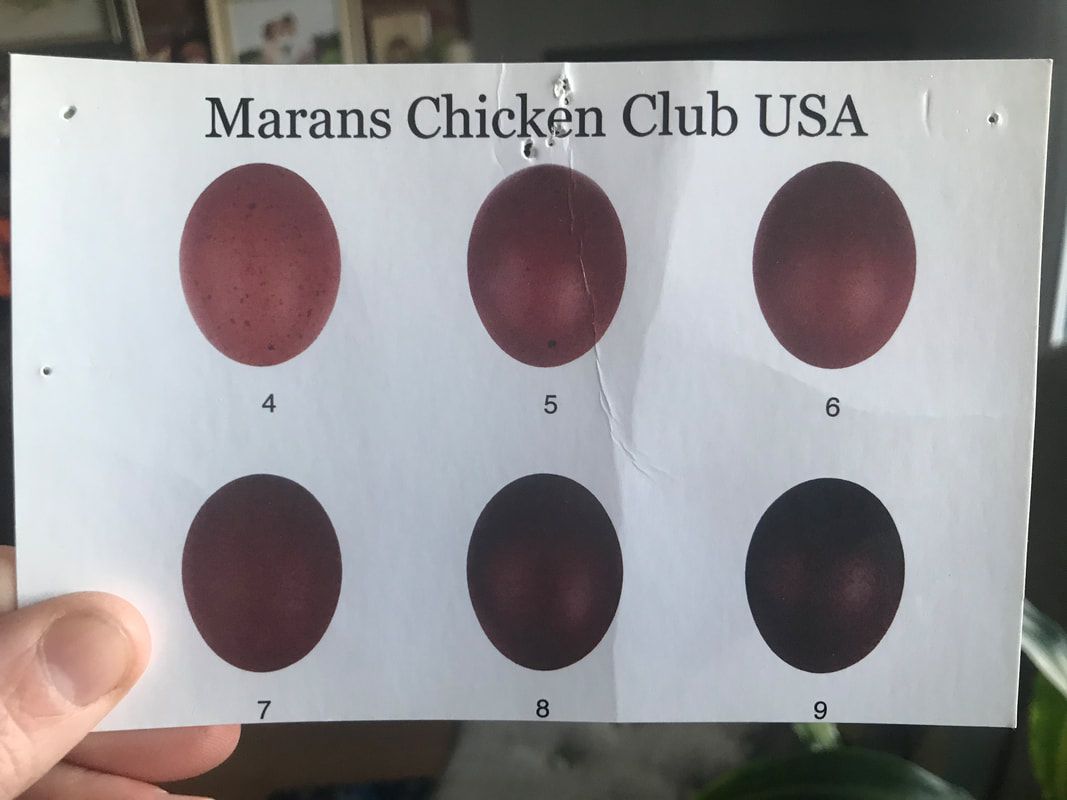

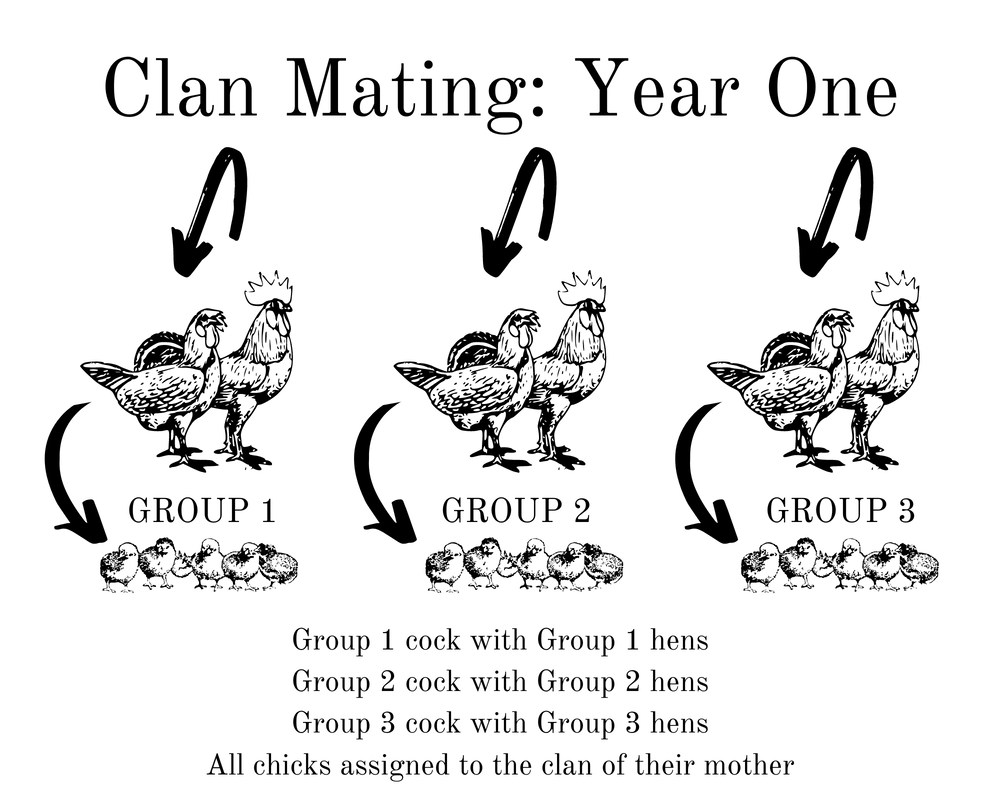

This speckled Marans beauty was our first new layer egg of the year. These pullet eggs aren’t much to eat, and they shouldn’t be hatched, but damn, they are magical--tiny hints of what’s to come, and always a thrill after months of nurturing a bird from hatch to point of lay. These eggs also mean it’s time to assess our first round of grow outs as we begin to make decisions about who will be part of our breeding programs next year. There’s a lot to think about with each bird. Assessing our growouts and breeding stock is a multi-layer, ongoing process. In this post, I’m going to chat about selective breeding and the things we take into consideration when making breeding decisions. This is by no means meant to be a comprehensive guide to breeding poultry--that is far too much for one blog post! Instead, I'll be sharing an overview that will give you some insight into everything we think about when making our breeding choices and what this process is like for us on our farm. The Standard of Perfection for PoultryPages from the Standard of Perfection. We really can't talk about breeding poultry without talking about the Standard of Perfection. Each officially recognized breed of poultry has its own Standard of Perfection, or goal that breeders of that particular bird are working toward. Even though it’s called the “Standard of Perfection,” you’ll often hear breeders say that “there is no perfect bird”. Breeding is a practice of slowing coaxing what you have toward your vision, generation after generation. It takes time and practice. In the United States, there is a Standard of Perfection for all poultry breeds recognized by the American Poultry Association (APA). Some breeds or varieties of breeds have not been officially accepted by the APA, which means those breeds and varieties don’t have an “official” standard. The Standard can vary somewhat from country to country. For example, both the US and French Standard for Marans calls for feathered shanks and outer toes, but the British Standard calls for clean legs. Confession time: I know a lot of breeders really enjoy breeding to the Standard for its own sake, but the Standard is not what drew me into breeding. I was called by the birds themselves, their personalities and my relationships with them. There was something about judging a creature and its value by the minute details of its appearance that really rubbed me the wrong way at first. At the same time, adhering to the Standard is a vital and important part of breeding, even if you don’t exhibit your birds. If there was no adherence to a Standard, breeds would become unrecognizable. While all of our birds have value and a place somewhere on the farm, only some of them can have a spot in our breeding programs. Diving into the Standard is to enter a world of detail, of paying attention, and learning about a different dimension of your birds. It’s an opportunity to hone your observation skills and study genetics. I consider myself a beginner and believe that I will remain a beginner for as long as I work with our birds, because there is always something new to learn. If you're interested in breeding your own poultry, I highly recommend investing in a copy of the Standard. You can order the most updated edition through the American Poultry Association. Defects and Disqualifications in ChickensThe Standard includes a wealth of information about breeding poultry, including everything you need to know about Defects and Disqualifications (DQs). These two terms can be easily confused, so I’m going to pull definitions right from the Standard: Defect: Anything short of perfection. Disqualification: A term applied to a deformity or a defect, sufficiently serious to disbar a fowl from an award, usually inherited. So basically, a defect is anything short of perfection, and a DQ is a defect so serious that a bird would be disqualified from receiving an award at a show. For defects that are not DQs, the Standard specifies how many points would be cut for each defect during judging at a show. Defects and DQs can be general, meaning that they apply to all breeds or groups of breeds. For example, things like a cross beak or roach back are DQs for all breeds. A side sprig is a DQ for all single combed breeds (a side sprig is a little growth on the side of the comb, swipe to see). A crooked toe won’t disqualify your bird, but it’s a general defect for all breeds and you’ll lose a point or two for it at show. Defects and DQs can also be specific to a breed. For example, yellow shanks or toes are a DQ for all Marans varieties, as are white earlobes and black eyes, even though those same features might be desirable in other breeds. Each Marans variety has its own DQs or defects, described in the Standard. We take all of this into account when considering our birds. When we do our first round of selections, we handle and observe our birds, looking for clear DQs and defects that would automatically remove them from consideration. We let the rest grow out longer and give them a chance to mature and show us what they’ve got. Breeding for TemperamentTemperament is a huge focus of our breeding program. My relationship with our roosters is one of my favorite parts of farming, and we want to breed birds that give others a good rooster experience, too. To that end, we hold our breeding boys to very high behavioral standards and don’t allow aggressive roosters in our breeding programs, no matter how gorgeous. I look for roosters that are gentle and respectful around humans, while still peppy and protective of their flock. That said, a few things I like to keep in mind: Culling for temperament doesn’t guarantee every roo we hatch will be gentle. Breeding is about progress, not perfection. Fortunately, selecting for temperament has given us a breeding program full of mostly gentle boys and most of our rooster culls are for cosmetic, not temperamental, reasons. Sometimes rooster aggression is inborn, and sometimes it’s situational, aka unwittingly caused by humans like myself. As flock leader, I need to respect my boys’ natural instincts and desire to protect their flock. I need to understand their view of the world. If I make loud noises or sudden movements, stare into their eyes, or handle their hens roughly in their presence, I am presenting myself as a threat and they might respond accordingly--even if their temperament is inherently gentle. Taking a rooster with a good temperament and actively working to develop a relationship of respect and trust is worth the time and effort. When I spend time with our roosters, handling them and getting to know them, our relationship moves from neutral into something truly magic. I don’t take culling for temperament lightly, because it’s a final decision. If a rooster looks at me funny, or gives my hand a peck, that’s not enough for me to cull. Instead, I consider it an invitation to work with them in order to repair a potential breach of trust or get to know their true nature. However, if a rooster comes at me with his spurs, one offense is all it takes. In my experience, aggressive roosters announce themselves with a pattern of behavior that increases in intensity over time. I listen to my instincts, as I find that my gut is often right about a rooster. Selecting for HealthHealth is another focus of our breeding program. If a bird has a health issue, we do our best to treat and care for them but they are removed from our breeding programs. There’s always a spot in our laying flock for birds that need a little extra TLC. Selecting for health and vigor begins at the moment of hatch. We don’t breed any birds that require help to hatch, since hatchability can be genetic and affect later generations. Chicks that need help hatching are shared with our community through our Chick Adoption Program or placed in our laying flock. We treat everything aside from an obvious injury as if it’s genetic, with the goal being to keep our breeding flocks as vigorous and healthy as possible. This goes for conditions that can have both external or genetic causes, like sour crop. Being disciplined in this way actually makes the decision making process easier. Looking at the StandardWe've talked about assessing birds based on temperament, health, and defects and disqualifications. These are pretty straightforward, yes-or-no judgements: Is this bird aggressive? Does it have health issues? Does it have any obvious physical defects? Once we’ve looked at our birds based on these criteria, I take a look at the remaining birds with the Standard in mind. This is actually more than one look; I like to give them a chance to grow out and see how they change over time. This phase of selection is a slow winnowing of the field over time, until we find the birds that most fit the Standard and our goals, and put our breeding groups together for the season. Some things I think about during this process: Build the Barn You might have heard breeders say things like “build the barn, then paint it.” This means always selecting for type first. Selecting for type (the basic form or shape of the bird) is more important than selecting for color or other small things that you can work over time. Handle the Birds It’s so important to handle and touch your birds as you assess them. This helps you find physical issues that aren’t clearly visible, like a crooked keel, but also helps you assess and compare birds, feeling and seeing things like depth of body and the wideness of their back. It also gives you insight into their temperament and comfort level with humans. Compare What You've Got Let’s be real: you can only work with what you’ve got. Maybe all your roosters have tails that are higher than you’d like, but one of them is going to have the lowest tail. Take the time to compare and consider your candidates as a group. We use a clan mating system, so I will compare birds from each clan to each other during the selection process. Look at Everything My first year of breeding, I made a little worksheet for myself to help me assess our birds. I listed every item from the Standard and made notes on how our birds measured up for every aspect. This way, I didn’t get mentally stuck on one particular feature, and it made it easy to remember my thoughts on that particular bird, and see any common issues. This system also helped me view each bird objectively and see clearly on paper how they measured up on the whole. Complementary Breeding and Locking in Traits Some birds have what the other lacks, and pairing these together can get you closer to your goals: for example, pairing a rooster with a high tail and a hen with a low tail. Or a Black Copper Marans rooster with leakage on his chest (color where it shouldn’t be) paired with a hen with very little copper can bring out more copper coloring in her daughters. In this way, imperfections can balance each other out. At the same time, if you find yourself with birds that share a desirable trait, pairing them together can help lock that trait in with later generations. What does it mean to cull?Culling can mean a couple different things, so if you see the word used in the context of breeding, keep that in mind. Culling can mean to kill, but it can also mean to remove from a breeding program. You might also hear someone say “hard cull” to refer to killing, and “soft cull” to refer simply to removal from a breeding program. We do both. We hard cull our extra roosters for food. Raising our own meat has been one of the most challenging and satisfying parts of this work. It was really hard to get started, because we were scared and didn’t know how. We’d also been vegetarian for years and years, so meat itself was kinda new, but it quickly became clear to us that our work as chicken keepers necessitated processing our own meat as well. We don’t raise meat birds specifically. I love the way our breeding programs create this little closed loop around meat for us. When making selections for our breeding programs, we wind up with extra roosters, but they are never really extra. They are a valuable piece of the puzzle that sustains us. Marans in particular are a great dual purpose breed. As all of you probably know by now, I’m in love with most roosters so we often “soft cull” a favorite rooster or two, if we have space for them. Currently we have two boys protecting our laying flock that we just couldn’t part with. As for hens and pullets, those are always soft culls here. If a pure breed hen doesn’t meet the standard *for her breed* but has no other issues or physical defects, then we will place her in our Olive Egger breeding program. This is another little loop--I love that we can make beautiful crosses out of “imperfections”. If a hen isn’t suitable for any of our breeding programs, she’ll have a home with our laying flock. Our laying flock provides us with eating eggs for our home and our farmstand, another little loop closed. It’s where all our beloved oddballs end up. So far we’ve had plenty of space for our girls to “age out” even as they get less productive, but at some point we may have to hard cull older hens. If we know at hatch that chicks won’t be suitable for our breeding program, then we place those birds into our Chick Adoption Program, where they will be rehomed locally. Whether it’s a soft cull or a hard cull, every bird is valued and has a place. Selecting for Eggs and Egg ColorI’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about eggs. Yes, eggs are definitely part of the selection process for me, and not just Marans egg color, though I will get to that. The quality of an egg is an important consideration for us as breeders. The Standard is important but our ultimate goal is to create birds that people love and help folks raise their own food. In the long run, selecting our birds based on the eggs they lay will help create more self-sustaining flocks. One the great parts of chicken keeping is the potential to have a self-contained, self-sustaining flock. If you have a rooster, you can hatch from your flock to replenish or grow your numbers. If you have reliable broodies, you might not even need special equipment. The one thing you do need, though, is quality hatching eggs. Not all eggs are created equal. Eggs that are oddly shaped or overly porous have a reduced chance of hatching successfully, and oddly shaped eggs can contribute to foot and leg issues if the chicks do hatch. We don’t set or sell oddball eggs. And while some hens will lay an unusual egg only once in a while, others are very consistent in laying unsuitable eggs. We select away from these less-than-stellar eggs in order to maintain hatching-quality eggs over time, and so our customers will have hatchable eggs in their flocks, too. With our Marans, there is the egg scale to follow that ranks shades of brown. A Marans egg needs to be a 4 or higher on the scale, so we are continually working on darker egg color for this breed, as well as shape and egg quality. Clan MatingThere are a number of breeding methods you can choose from as a breeder. We’ve chosen to use a Clan Mating system as our breeding framework. Clan Mating, also known as Spiral Mating, is the breeding system we use on the farm for our Self Blue Ameraucanas and Black Copper Marans. It’s a simple mating system of at least three groups, or clans. Offspring always belong to the clan of their mother. After an initial year of mating within the clan, cocks from one clan are rotated over to the next, year after year. Like any breeding program, there are pros and cons. Some of the things that initially attracted us to Clan Mating were:

The main drawback of clan mating is that it can take longer to see results, compared to a method that concentrates genetics more quickly, like line breeding. Clan mating can also be used as a great maintenance program after using other methods. This method is a great fit for us, for all the reasons above, and it can be a great way to keep your own backyard flock going for decades to come. If you'd like to know more about Clan Mating, I wrote a blog post detailing what clan mating is and how to begin your own program, even if you just have a breeding pair to start with, plus the pros and cons of clan mating. I also share the tools and steps we use to keep track of our birds’ clans from egg to maturity, and included some printable clan mating how-to graphics and a record-keeping sheet. Parting ThoughtsAs someone who didn’t grow up on a farm, never did 4-H or showed poultry, diving into breeding definitely felt a little intimidating. It’s a whole world unto itself, with endless learning opportunities. While there’s a lot to learn, it’s also incredibly satisfying to see your flocks improve with time, and know that the decisions you’re making are paying off.

If the world of breeding calls to you, I encourage you to try it out (the joy of hatching chicks alone is worth it!). A few parting thoughts, for those of you interested in breeding:

Thank you so much for reading. I hope this post gave you some insight into our selective breeding process. If you have any questions, please share in the comments!

4 Comments

Angie

7/31/2022 10:08:37 am

Your logic on breeding opposite tail faults to balance them out is ridiculous, you just bred two birds that should have been culled and you just made worse birds, now you’ll get high AND low tails and reduced your odds of a good tail. At least one of the birds should have a perfect tail set and then you would cull all of the defective offspring and breed the best offspring back to the perfect tail parent and go from there, always culling the defects.

Reply

Thewildchickenfarm

4/25/2024 09:19:24 pm

I agree, it is a common myth that breeding two opposites together fixes the trait, the only thing it dose is gives you both of the defects, one look at polygenics and you would know that, instead it is far better to select the two closest to perfect you have and breed them, if it's really a problem (eg, like your whole flock has squirrel tail) then start a sibline to concentrate on that trait only while keeping up the normal selection on the rest of your flock.

Reply

1/30/2023 11:33:24 am

Thank you for sharing your experience! This was an incredibly informative and well written article 🙏🏻

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Hi, I'm Maeg.Welcome to our blog! Categories

All

|

©

The Silver Fox Farm